A Gentle Introduction to Ray Core by Example#

Implement a function in Ray Core to understand how Ray works and its basic concepts. Python programmers from those with less experience to those who are interested in advanced tasks, can start working with distributed computing using Python by learning the Ray Core API.

Install Ray#

Install Ray with the following command:

! pip install ray

Ray Core#

Start a local cluster by running the following commands:

import ray

ray.init()

Note the following lines in the output:

... INFO services.py:1263 -- View the Ray dashboard at http://127.0.0.1:8265

{'node_ip_address': '192.168.1.41',

...

'node_id': '...'}

These messages indicate that the Ray cluster is working as expected. In this example output, the address of the Ray dashboard is http://127.0.0.1:8265. Access the Ray dashboard at the address on the first line of your output. The Ray dashboard displays information such as the number of CPU cores available and the total utilization of the current Ray application.

This is a typical output for a laptop:

{'CPU': 12.0,

'memory': 14203886388.0,

'node:127.0.0.1': 1.0,

'object_store_memory': 2147483648.0}

Next, is a brief introduction to the Ray Core API, which we refer to as the Ray API. The Ray API builds on concepts such as decorators, functions, and classes, that are familiar to Python programmers. It is a universal programming interface for distributed computing. The engine handles the complicated work, allowing developers to use Ray with existing Python libraries and systems.

Your First Ray API Example#

The following function retrieves and processes

data from a database. The dummy database is a plain Python list containing the

words of the title of the “Learning Ray” book.

The sleep function pauses for a certain amount of time to simulate the cost of accessing and processing data from the database.

import time

database = [

"Learning", "Ray",

"Flexible", "Distributed", "Python", "for", "Machine", "Learning"

]

def retrieve(item):

time.sleep(item / 10.)

return item, database[item]

If the item with index 5 takes half a second (5 / 10.), an estimate of the total runtime to retrieve all eight items sequentially is (0+1+2+3+4+5+6+7)/10. = 2.8 seconds.

Run the following code to get the actual time:

def print_runtime(input_data, start_time):

print(f'Runtime: {time.time() - start_time:.2f} seconds, data:')

print(*input_data, sep="\n")

start = time.time()

data = [retrieve(item) for item in range(8)]

print_runtime(data, start)

Runtime: 2.82 seconds, data:

(0, 'Learning')

(1, 'Ray')

(2, 'Flexible')

(3, 'Distributed')

(4, 'Python')

(5, 'for')

(6, 'Machine')

(7, 'Learning')

The total time to run the function is 2.82 seconds in this example, but time may be different for your computer. Note that this basic Python version cannot run the function simultaneously.

You may expect that Python list comprehensions are more efficient. The measured runtime of 2.8 seconds is actually the worst case scenario. Although this program “sleeps” for most of its runtime, it is slow because of the Global Interpreter Lock (GIL).

Ray Tasks#

This task can benefit from parallelization. If it is perfectly distributed, the runtime should not take much longer than the slowest subtask,

that is, 7/10. = 0.7 seconds.

To extend this example to run in parallel on Ray, start by using the @ray.remote decorator:

import ray

@ray.remote

def retrieve_task(item):

return retrieve(item)

With the decorator, the function retrieve_task becomes a :ref:ray-remote-functions<Ray task>_.

A Ray task is a function that Ray executes on a different process from where

it was called, and possibly on a different machine.

Ray is convenient to use because you can continue writing Python code,

without having to significantly change your approach or programming style.

Using the :func:ray.remote()<@ray.remote> decorator on the retrieve function is the intended use of decorators,

and you did not modify the original code in this example.

To retrieve database entries and measure performance, you do not need to make many changes to the code. Here’s an overview of the process:

start = time.time()

object_references = [

retrieve_task.remote(item) for item in range(8)

]

data = ray.get(object_references)

print_runtime(data, start)

2022-12-20 13:52:34,632 INFO worker.py:1529 -- Started a local Ray instance. View the dashboard at 127.0.0.1:8265

Runtime: 0.71 seconds, data:

(0, 'Learning')

(1, 'Ray')

(2, 'Flexible')

(3, 'Distributed')

(4, 'Python')

(5, 'for')

(6, 'Machine')

(7, 'Learning')

Running the task in parallel requires two minor code modifications.

To execute your Ray task remotely, you must use a .remote() call.

Ray executes remote tasks asynchronously, even on a local cluster.

The items in the object_references list in the code snippet do not directly contain the results.

If you check the Python type of the first item using type(object_references[0]),

you see that it is actually an ObjectRef.

These object references correspond to futures for which you need to request the result.

The call :func:ray.get()<ray.get(...)> is for requesting the result. Whenever you call remote on a Ray task,

it immediately returns one or more object references.

Consider Ray tasks as the primary way of creating objects.

The following section is an example that links multiple tasks together and allows

Ray to pass and resolve the objects between them.

Let’s review the previous steps.

You started with a Python function, then decorated it with @ray.remote, making the function a Ray task.

Instead of directly calling the original function in the code, you called .remote(...) on the Ray task.

Finally, you retrieved the results from the Ray cluster using .get(...).

Consider creating a Ray task from one of your own functions as an additional exercise.

Let’s review the performance gain from using Ray tasks. On most laptops the runtime is around 0.71 seconds, which is slightly more than the slowest subtask, which is 0.7 seconds. You can further improve the program by leveraging more of Ray’s API.

Object Stores#

The retrieve definition directly accesses items from the database. While this works well on a local Ray cluster, consider how it functions on an actual cluster with multiple computers.

A Ray cluster has a head node with a driver process and multiple worker nodes with worker processes executing tasks.

In this scenario the database is only defined on the driver, but the worker processes need access to it to run the retrieve task.

Ray’s solution for sharing objects between the driver and workers or between workers is to use

the ray.put function to place the data into Ray’s distributed object store.

In the retrieve_task definition, you can add a db argument to pass later as the db_object_ref object.

db_object_ref = ray.put(database)

@ray.remote

def retrieve_task(item, db):

time.sleep(item / 10.)

return item, db[item]

By using the object store, you allow Ray to manage data access throughout the entire cluster.

Although the object store involves some overhead, it improves performance for larger datasets.

This step is crucial for a truly distributed environment.

Rerun the example with the retrieve_task function to confirm that it executes as you expect.

Non-blocking calls#

In the previous section, you used ray.get(object_references) to retrieve results.

This call blocks the driver process until all results are available.

This dependency can cause problems if each database item takes several minutes to process.

More efficiency gains are possible if you allow the driver process to perform other tasks while waiting for results,

and to process results as they are completed rather than waiting for all items to finish.

Additionally, if one of the database items cannot be retrieved due to an issue like a deadlock in the database connection,

the driver hangs indefinitely.

To prevent indefinite hangs, set reasonable timeout values when using the wait function.

For example, if you want to wait less than ten times the time of the slowest data retrieval task,

use the wait function to stop the task after that time has passed.

start = time.time()

object_references = [

retrieve_task.remote(item, db_object_ref) for item in range(8)

]

all_data = []

while len(object_references) > 0:

finished, object_references = ray.wait(

object_references, timeout=7.0

)

data = ray.get(finished)

print_runtime(data, start)

all_data.extend(data)

print_runtime(all_data, start)

Runtime: 0.11 seconds, data:

(0, 'Learning')

(1, 'Ray')

Runtime: 0.31 seconds, data:

(2, 'Flexible')

(3, 'Distributed')

Runtime: 0.51 seconds, data:

(4, 'Python')

(5, 'for')

Runtime: 0.71 seconds, data:

(6, 'Machine')

(7, 'Learning')

Runtime: 0.71 seconds, data:

(0, 'Learning')

(1, 'Ray')

(2, 'Flexible')

(3, 'Distributed')

(4, 'Python')

(5, 'for')

(6, 'Machine')

(7, 'Learning')

Instead of printing the results, you can use the retrieved values

within the while loop to initiate new tasks on other workers.

Task dependencies#

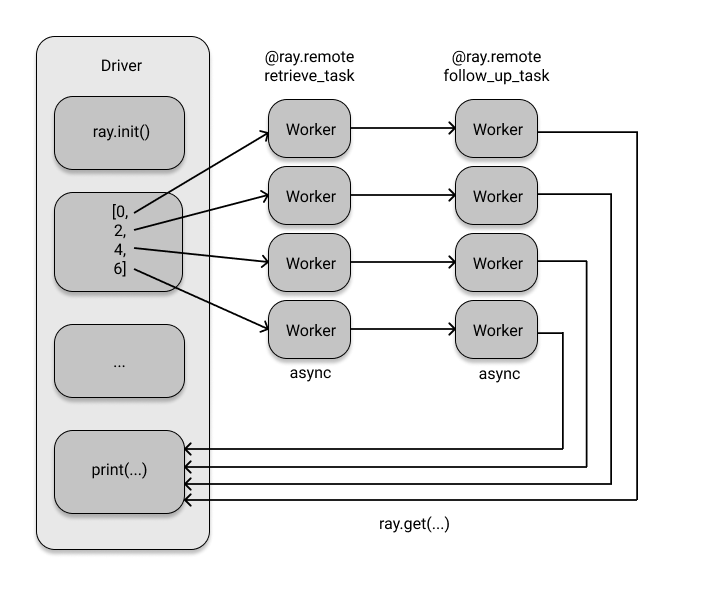

You may want to perform an additional processing task on the retrieved data. For example,

use the results from the first retrieval task to query other related data from the same database (perhaps from a different table).

The code below sets up this follow-up task and executes both the retrieve_task and follow_up_task in sequence.

@ray.remote

def follow_up_task(retrieve_result):

original_item, _ = retrieve_result

follow_up_result = retrieve(original_item + 1)

return retrieve_result, follow_up_result

retrieve_refs = [retrieve_task.remote(item, db_object_ref) for item in [0, 2, 4, 6]]

follow_up_refs = [follow_up_task.remote(ref) for ref in retrieve_refs]

result = [print(data) for data in ray.get(follow_up_refs)]

((0, 'Learning'), (1, 'Ray'))

((2, 'Flexible'), (3, 'Distributed'))

((4, 'Python'), (5, 'for'))

((6, 'Machine'), (7, 'Learning'))

If you’re unfamiliar with asynchronous programming, this example may not be particularly impressive. However, at second glance it might be surprising that the code runs at all. The code appears to be a regular Python function with a few list comprehensions.

The function body of follow_up_task expects a Python tuple for its input argument retrieve_result.

However, when you use the [follow_up_task.remote(ref) for ref in retrieve_refs] command,

you are not passing tuples to the follow-up task.

Instead, you are using the retrieve_refs to pass in Ray object references.

Behind the scenes, Ray recognizes that the follow_up_task needs actual values,

so it automatically uses the ray.get function to resolve these futures.

Additionally, Ray creates a dependency graph for all the tasks and executes them in a way that respects their dependencies.

You don’t have to explicitly tell Ray when to wait for a previous task to be completed––it infers the order of execution.

This feature of the Ray object store is useful because you avoid copying large intermediate values

back to the driver by passing the object references to the next task and letting Ray handle the rest.

The next steps in the process are only scheduled once the tasks specifically designed to retrieve information are completed.

In fact, if retrieve_refs was called retrieve_result, you might not have noticed this crucial and intentional naming nuance. Ray allows you to concentrate on your work rather than the technicalities of cluster computing.

The dependency graph for the two tasks looks like this:

Ray Actors#

This example covers one more significant aspect of Ray Core.

Up until this step, everything is essentially a function.

You used the @ray.remote decorator to make certain functions remote, but aside from that, you only used standard Python.

If you want to keep track of how often the database is being queried, you could count the results of the retrieve tasks. However, is there a more efficient way to do this? Ideally, you want to track this in a distributed manner that can handle a large amount of data. Ray provides a solution with actors, which run stateful computations on a cluster and can also communicate with each other. Similar to how you create Ray tasks using decorated functions, create Ray actors using decorated Python classes. Therefore, you can create a simple counter using a Ray actor to track the number of database calls.

@ray.remote

class DataTracker:

def __init__(self):

self._counts = 0

def increment(self):

self._counts += 1

def counts(self):

return self._counts

The DataTracker class becomes an actor when you give it the ray.remote decorator. This actor is capable of tracking state,

such as a count, and its methods are Ray actor tasks that you can invoke in the same way as functions using .remote().

Modify the retrieve_task to incorporate this actor.

@ray.remote

def retrieve_tracker_task(item, tracker, db):

time.sleep(item / 10.)

tracker.increment.remote()

return item, db[item]

tracker = DataTracker.remote()

object_references = [

retrieve_tracker_task.remote(item, tracker, db_object_ref) for item in range(8)

]

data = ray.get(object_references)

print(data)

print(ray.get(tracker.counts.remote()))

[(0, 'Learning'), (1, 'Ray'), (2, 'Flexible'), (3, 'Distributed'), (4, 'Python'), (5, 'for'), (6, 'Machine'), (7, 'Learning')]

8

As expected, the outcome of this calculation is 8. Although you don’t need actors to perform this calculation, this demonstrates a way to maintain state across the cluster, possibly involving multiple tasks. In fact, you could pass the actor into any related task or even into the constructor of a different actor. The Ray API is flexible, allowing for limitless possibilities. It’s rare for distributed Python tools to allow for stateful computations, which is especially useful for running complex distributed algorithms such as reinforcement learning.

Summary#

In this example, you only used six API methods.

These included ray.init() to initiate the cluster, @ray.remote to transform functions and classes into tasks and actors,

ray.put() to transfer values into Ray’s object store, and ray.get() to retrieve objects from the cluster.

Additionally, you used .remote() on actor methods or tasks to execute code on the cluster, and ray.wait to prevent blocking calls.

The Ray API consists of more than these six calls, but these six are powerful, if you’re just starting out. To summarize more generally, the methods are as follows:

ray.init(): Initializes your Ray cluster. Pass in an address to connect to an existing cluster.@ray.remote: Turns functions into tasks and classes into actors.ray.put(): Puts values into Ray’s object store.ray.get(): Gets values from the object store. Returns the values you’ve put there or that were computed by a task or actor..remote(): Runs actor methods or tasks on your Ray cluster and is used to instantiate actors.ray.wait(): Returns two lists of object references, one with finished tasks we’re waiting for and one with unfinished tasks.

Want to learn more?#

This example is a simplified version of the Ray Core walkthrough of our “Learning Ray” book. If you liked it, check out the Ray Core Examples Gallery or some of the ML workloads in our Use Case Gallery.